With rooftop solar, it's not just about the carbon reduction

A condended version of this post was first published in The Hill on Oct 8, 2021.

The Biden administration recently unveiled a plan for a steep increase in the nation’s share of electricity generated from the sun. That is good news. Solar-generated electricity reduces carbon emissions, just like wind. There is also a climate change-related benefit of solar energy that wind does not have, one that is much more immediate: resiliency to blackouts during extreme weather events.

But the plan favors utility companies over individual homeowners and that is a mistake.

Rooftop solar panels equipped with a backup battery can be one of the best tools to provide electricity during blackouts caused by extreme weather , potentially preventing loss of life. One example: After Hurricane Ida

Hurricane Ida made landfall in the USA at the end of August, 2021. According to the wikipedia entry for Ida, "Hurricane Ida was a deadly and destructive Category 4 Atlantic hurricane that became the second-most damaging and intense hurricane to make landfall in the U.S. state of Louisiana on record, behind Hurricane Katrina in 2005.".

knocked out the power in Louisiana, more people died from heat-related health problems than from the storm directly .

The Biden plan seems to de-emphasize rooftop solar panels in favor of utility-scale solar plants — large fields with lots of photovoltaic panels. The Department of Energy's "solar futures" report upon which the administration’s plan is based states that rooftop solar energy will account for about 10 percent to 20 percent of all solar by 2050, down from 33 percent at present. So according to the administration's plan, utility-scale solar plants will play a bigger role in the future than rooftop solar panels.

Of course, the plan will probably be better accepted by utility companies. After all, they have pitched political battles to prevent rooftop solar panel adoption. Lost revenue is just one issue for them. A second issue is that the intermittent generation from solar panels make operating the power grid more challenging. A utility-scale solar power plant is a more controllable — and thus more useful — resource to the utility than thousands of rooftop systems over which the utility has no control.

So what can be done to encourage adoption of rooftop solar panel systems to aid climate resiliency without running into opposition from utility companies?

A solution would be to equip homes with small rooftop solar panels and an appropriately sized battery. When there is a blackout due to an extreme weather event, such as a hurricane or flood, the panels and the battery will provide critical energy service. Sure, it won’t be enough to run an air conditioner full blast, but it will be enough to preserve medicine and food in the refrigerator and operate a few ceiling fans and lights. Energy generated during routine times will help meet the nation's carbon reduction goals. But the small capacity of the panels means utilities won’t have to fear a large loss in revenue. Also, software can use the battery to reduce the fluctuations seen by the power grid, ameliorating the second concern of the utility companies.

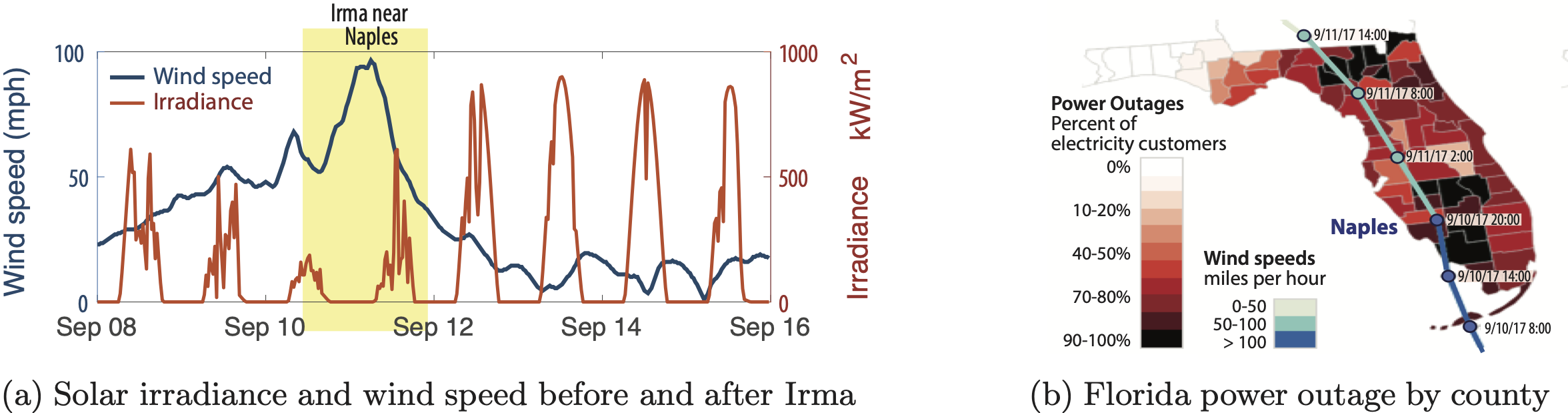

Some may wonder how rooftop solar panels fare in a hurricane. Funny enough, that is not a concern for the majority of people affected by hurricanes. The TV images of roofs being blown to bits is true only for a small fraction of homes. When Hurricane Irma hit Southeastern USA in 2017, 60 percent of Florida residents lost electricity but only 7 percent of homes suffered any kind of roof damage.

See the long footnote at the bottom of this page for the analysis behind the 7% estimate.

Second, the sky is often clear immediately after a hurricane, as the picture below shows. That means solar panels are a great source of electricity after a weather-induced blackout.

The primary bottleneck to adoption of these systems has been cost. However, the cost and benefit calculations currently used for rooftop solar panels are based purely on the dollar cost of the energy generated during normal operation, ignoring all other aspects such as carbon reduction and generation variability the grid must absorb. They also overlook improvements in solar panel and battery technology that will continue to reduce costs.

The battery can be used to smooth out the volatility of power demand placed on the power grid by the residence. The technology for doing so already exists. Reducing volatility of energy draw from the power grid directly translates to savings for the utility companies.

And the life-saving potential of rooftop solar systems equipped with battery backup during a disaster is assigned zero value. The same kind of short-sighted economic calculation that has led to the climate crisis is at play here.

This is why reframing the benefits of solar is necessary. Let’s incentivize homeowners to install smaller capacity rooftop solar panels with battery backup, providing each homeowner with some protection against blackouts. Utilities will benefit because they will be under less pressure to make their networks storm resistant, which is prohibitively expensive. The smaller capacity of rooftop solar panels will reduce the perceived threat to utility companies’ bottom lines. All of these will drive wider adoption, which will aid the Biden administration's plan to increase solar power as a resource in the electricity mix.